AI preparedness for knowledge-based organisations

A version of this blog post was originally published on 21 April 2024 on the On Think Tanks website.

Over the last two years, the growth in the capabilities of generative artificial intelligence (AI) has captured the world’s imagination. But, for organisations in the knowledge economy, leaning into the technology has generally been more opportunistic than strategic.

The challenge has typically been around deciding what angle to approach it from. I’ve been interested in AI for many years, but I’ve been formally involved in AI now for 18 months.

Over that time, the field has become so rich and diverse that it makes as little sense to say “I work in AI” as it does to say “I work in the internet”.

Do you mean you’re involved in building LLMs [large language models]? Or do you work in AI ethics? Are you a digital transformation professional, trying to roll out AI projects across your organisation? Are you a developer looking to build chatbots on top of foundation models? Or maybe you’re a data strategist looking to leverage your organisation’s data? A policy-maker thinking about AI regulation? A child safety campaigner concerned about deepfakes?

It is a complex and multi-faceted technology, and its applications are potentially so ubiquitous that some people have been comparing it to electricity.

And just as it’s hard to imagine how an ‘electricity expert’ in the 19th century might answer the question, “What should my unconnected organisation do about electricity?”, so it goes for AI.

With all the hype in our feeds, it’s easy to think that everyone is ‘doing AI’, and that you’re being left behind. In the world of think tanks, they’re not – and you’re not (yet).

This blog post seeks to provide an answer for professionals who are wondering: How should I approach AI? How do I get my organisation ready in a proactive way, but without succumbing to the hysteria?

The chaotic approach to AI

If your LinkedIn feed is anything like mine, it probably looks something like this:

The AI chaos that lies in our feeds (Daimon Communications 2024).

It’s a lot. It’s disparate. It’s chaotic. As a result, you could be forgiven for not knowing what angle to grab it by.

Take my case as an example. Beyond my unconscious everyday use of AI through the likes of Alexa’s virtual assistant, Google Maps or Netflix’s algorithm, I also do the following:

I’ve been running experiments with AI to optimise my own workflow

I’ve been advising clients on opportunities to influence AI results

I’ve been involved in the debate around AI safety and disinformation

I co-founded a network of professionals interested in AI policy and advocacy (it’s called Appraise, go and check it out!)

The thing is, these activities are only loosely connected, in the same way that using a laptop, designing a motherboard and implementing energy policy are all connected by electricity. I could be pursuing each of these endeavours on its own, with little to no impact on the others.

So, in this chaos, how do I decide what to focus on? In strategic terms, what are the opportunity costs?

Personally, I can deal with uncertainty – but my brain hates chaos. This has led me, throughout my career, to build mind maps and frameworks to help me make sense of the world. The next section sets out the framework I’ve designed for myself around AI.

If you’re thinking about how to make your organisation AI-ready, this may be useful to you.

A framework for bringing order to the AI chaos

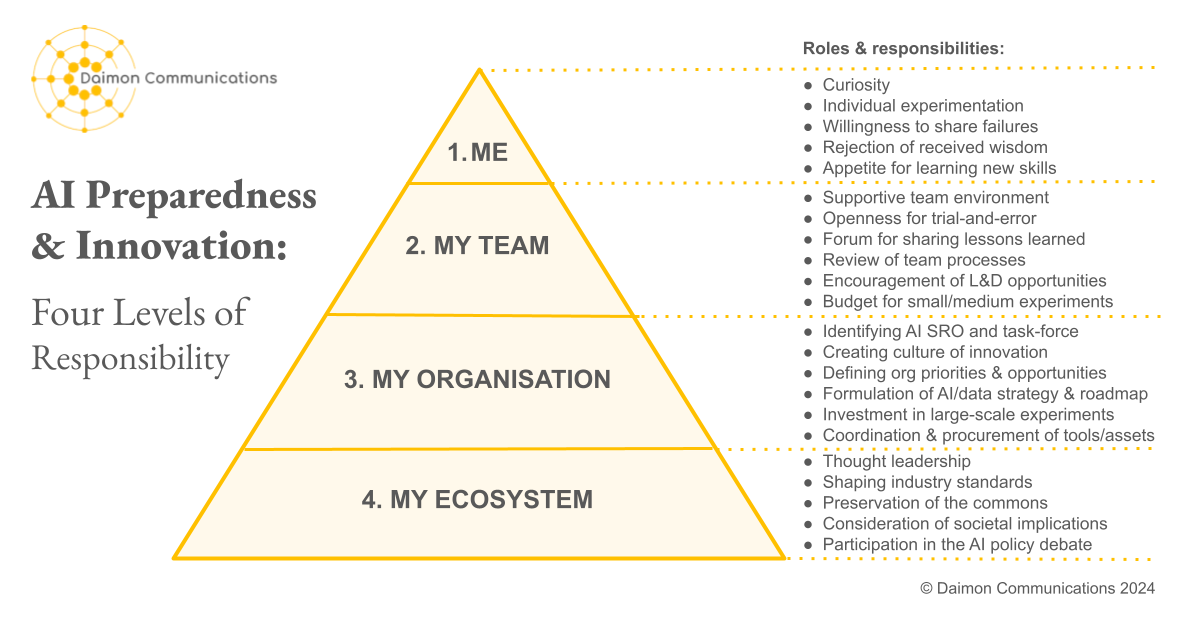

This is how I think of AI and the different levels we need to focus on:

AI Preparedness & Innovation: Four Levels of Responsibility (Daimon Communications 2024).

Before going into each of the four levels of responsibility, it is worth recognising that I work with knowledge-based organisations, and that this framework was developed with them in mind – as opposed to manufacturers, consumer companies or AI companies themselves.

Secondly, the framework has been conceived from the point–of–view of professionals looking to shape their organisation’s early approach to AI. In other words, it is for comms, research, operations or corporate professionals, and might have less relevance for data scientists, engineers or web developers.

Thirdly, the field of AI is still young. It has evolved significantly over the last two years and it will continue to change. This framework will, no doubt, have to evolve with it over the coming years.

The four levels of responsibility for AI innovation

For professionals looking to help their organisation lean into AI, here are the levels at which AI needs to be considered. Your job as a leader is to think about how you can influence each of these:

1. AI innovation by individual employees

Many employees will be thinking about how they can use AI to facilitate daily tasks. The specific form this innovation takes will depend on the function in which they work – whether it’s comms, research, finance, recruitment, HR, or anything else.

This is where we have seen the bulk of experimentation to–date: prompt engineering, copy generation, image generation, text-to-video, content planning, coding and data analysis.

The best way for an employee to future-proof their role is to start using the technology, look for training opportunities where they exist, and be open to sharing experiments that failed.

Most of the practical posts in my LinkedIn feed relate to this level. This is probably due to the low barriers to entry, but also to the lack of understanding at more senior levels of how to approach AI innovation at an organisational level.

2. AI innovation at a team level

Individual team members need to feel empowered to innovate – they must adopt a trial-and-error approach and get comfortable with failure. For this to happen, team leaders must foster a culture of innovation: a safe environment for their team members to try things out. This includes giving them permission to fail without the fear of being judged negatively.

Another role for team leaders is to facilitate the sharing of findings and lessons learnt across the team (for example, lunch-and-learns and how-to guides) and be a champion for the team’s experiments at an organisational level.

The team – and the organisation as a whole – will initially learn more from failed experiments than they will from successes. Leaders must set that expectation.

In the medium term, team leaders also have a duty to review their team’s processes and identify priority areas for the roll-out of AI across the team’s activities.

This should include allocating some budget for experiments that may require a little investment and a separate budget for learning and development (L&D) or training opportunities for champions within the team.

Importantly, champions should have the skills, authority and enthusiasm to drive change – it should not simply fall to junior team members just because they are young.

3. AI innovation at an organisational level

Organisation-level innovation should be concerned with big-ticket changes, which require one of the following:

A cultural change across the organisation, such as, the redefinition of a key service or product.

A digital transformation process, which typically requires investment– such as automating a service, building your own AI bots, influencing AI results, or procuring third-party AI-powered software.

Many organisations have tried to lean into AI by creating some form of AI task-force, trying to channel individual innovation rather than driving innovation from the top.

Given that most executive teams do not yet have the knowledge and skills to make informed decisions, crowd-sourcing innovation is not a bad place to start. But it does not constitute a long-term strategy.

While every team member has a contribution to make in terms of AI innovation, it needs a figurehead to champion the innovation culture, coordinate across teams, decide on priorities, drive big-ticket changes and achieve economies of scale.

Experience shows that if innovation is everyone’s responsibility, it is ultimately no-one’s responsibility. A good first step is to name a senior responsible owner (SRO). Someone with the skills, authority and enthusiasm – not just someone who has the capacity!

The SRO should be given licence to create and incentivise that innovation culture across the organisation and to communicate this to employees.

Along with the CEO, they should also have a role in reassuring employees that they are not innovating themselves out of jobs.

Crucially, the SRO should be setting the direction of travel for the organisation over the coming years (a roadmap); identifying immediate and long-term organisational priorities and opportunities (a strategy); and allocating budget to the most promising or pressing initiatives (a plan).

4. Monitoring AI’s impact on your ecosystem

AI is not going to be released into a vacuum. Although the technology has the potential to do untold good, an irresponsible roll-out of the technology will carry a number of risks.

Firstly, we need to be aware of unexpected consequences in our ecosystems. By definition, we do not know what these are, but being aware that these will probably arise and monitoring our environment is not a bad start.

Secondly, there are harms that we can expect. We know, for example, that AI has the potential to further undermine the health of the information environment that think tanks rely on.

AI will also, no doubt, represent a threat to the livelihoods of multiple professions represented by chartered bodies, or to the safety of multiple groups represented by charities and non-governmental organisations.

The debate on AI policy and regulation is set to be a backdrop to our professional lives for the next decade, at least. But it is worth remembering the debate is still in its infancy, and AI policy and regulation are yet to be determined.

Think tanks, and indeed all organisations involved in the knowledge economy, should feel a responsibility – not to mention a self-interested need – to play a part in shaping these new norms.

Taking your first steps towards AI preparedness

So, how can knowledge-based organisations prepare for an undefined future, with so many moving parts?

Well, there are some parallels here with the practice of crisis preparedness. While we might not know the exact form the crisis will take, we can make predictions on what we will need based on the common features of most crises.

Similarly, we can draw on the experiences of recent technological revolutions – such as, digital, social media, data and mobile – to predict what think tanks will need.

Here are a few recommendations for taking your first steps towards AI preparedness:.

For employees:

Be curious and be open to failure

Experiment with AI

Share your findings

Volunteer for training

For team leaders:

Create a safe environment for team members to experiment (and fail)

Identify L&D opportunities for your team members

Set aside a small budget to support team members’ experiments

Review team processes and identify priorities and opportunities

For organisation leaders:

Name an SRO and an AI task force

Create and incentivise a culture of innovation

Mandate budgets for AI training and experimentation across teams

Review organisational processes and develop an AI/data strategy and roadmap

Develop an organisation-wide AI policy for employees to set expectations on AI use

Invest in medium–/large-scale experiments or builds

Conduct or commission a scoping exercise to identify third-party AI tools

Conduct or commission an audit of your organisation’s online footprint, and a content strategy to influence AI results

Develop a thought leadership platform and get involved in the debate on AI policy

Get in touch with me via LinkedIn for a presentation on UK MPs’ perceptions of AI