How policy experts can use language to set the agenda

This blog post was originally published on 20 January 2022 on the Cast From Clay website.

On 11 March 2003, US Rep. Bob Ney instructed the three cafeterias that served the House of Representatives to no longer refer to ‘French fries’ or ‘French toast’. Instead, the cafeteria menus were to list them as ‘Freedom fries’ and ‘Freedom toast’.

Ney was the Chairman of the US House Committee on House Administration. Just three weeks earlier, French Foreign Affairs Minister Dominique de Villepin had stood up in front of the UN Security Council, and delivered a heart-felt speech opposing the US’s proposed invasion of Iraq. This had angered the more hawkishly-inclined Republicans in the House.

Menu from a Congressional cafeteria featuring freedom fries. © Creative Commons

In his statement about the rebrand of said carbohydrates, Ney explained: “This action today is a small but symbolic effort to show the strong displeasure many on Capitol Hill have with our so-called ally, France.”

The measure was met with derision in France. In response, the French Embassy spokeswoman commented: “It’s exactly a non-issue… We focus on the serious issues… We are not focusing on the name [Americans] give to potatoes.”

However, it pointed to something more fundamental that the Republicans had understood: words have the power to frame key issues.

Defining the language of victory

The stage had been set for the Freedom Fry at least a decade before.

In 1994 – 2 years into Bill Clinton’s presidency – Newt Gingrich set out to redefine the lexicon of the Republican Right. Through his Contract with America, he identified the flagship issues which Americans really cared about.

The book was written with the help of Republican pollster Frank Luntz, who market-tested how Republican candidates should be talking about issues, policies and legislation, in order to create emotional resonance with the American public.

The research explored words, phrases, metaphors. ‘Tax cuts’ became ‘tax relief’. ‘Foreign investment’ became ‘international investment’. Bills were given evocative names like the ‘Personal Responsibility Act’ (for welfare reform), or the ‘Taking Back Our Streets Act’ (for criminal justice reform).

This was a masterclass in framing. By giving their proposed policy interventions media-friendly names, the Republicans were seizing control of language used – and by so doing, dictating the terms of the debate. By definition, framing – when successful – shapes what is out of scope, what is in scope, and the potential remedial action.

This approach provided a blueprint for Republican communications which ultimately carried George W. Bush to victory in 2000. And it still shapes GOP language to this day.

Language shapes our thinking at a subconscious level

This struggle for the linguistic high-ground is perhaps most vividly demonstrated within the context of the abortion debate in the US, with campaigners characterising their positions as ‘pro-life’ and ‘pro-choice’.

Tellingly, some pro-choice campaigners are rejecting the pro-life camp’s framing by calling them ‘anti-choice’ instead. How can you call yourself pro-life, they ask, when you’re promoting policies that favour high infant and maternal mortality, or that deny support for hungry children?

Of course, abortion is a high-profile and highly emotional debate between two ideologically-entrenched camps. Surely the more run-of-the-mill policy debate, between policy experts and policy makers, isn’t subject to these dynamics?

Well, maybe. But it feels like too important a consideration to leave to chance. Language matters far more than we even realise – in some instances, more than our personal political persuasions.

Framing – when successful – shapes what is out of scope, what is in scope, and the potential remedial action.

A study in 2011 showed that picking the right metaphor could shape people’s attitudes to policy. In the experiment, a crime trend was described to one group as a ‘beast preying’ on the city, and to another group as a ‘virus infecting’ the city.

The idea was to explore whether participants would propose treating the crime issue in the same way they might approach a literal epidemic (i.e. through social reforms, prevention, education), versus how they would tackle a literal beast (i.e. capturing, caging, killing).

And indeed, participants exposed to the ‘beast’ metaphor were more likely to believe crime should be met punitively, while those exposed to the ‘virus’ metaphor were more likely to support reformative measures.

The metaphor was a better predictor of participants’ response to the issue even than their political allegiance. But crucially, when asked, none of them were able to identify why they felt the way they did. They were more likely to point to the statistics, for example, even though they were the same for both groups.

Recommendations for policy experts and communicators

The examples above show that language can influence policy outcomes. The first step to leveraging that insight is to acknowledge that, while the quality of the data or research matters, the success of a policy recommendation does not rest solely on these factors.

Owning the vocabulary of the policy debate will help us create the outcomes we desire. It will also have the associated benefit of making our impact easier to prove. If we’ve shaped the language of the debate, we can lay a good claim to having set the agenda – and in a measurable way.

Here are a few examples of how policy professionals can seize control of the debate.

1. Coin phrases that describe your key concepts

Policy ideas are often based on key concepts. By inserting these into the debate, we are subconsciously legitimising them, along with the assumptions on which they are based.

For example, one of the great policy communication successes over the last decade has been the Carbon Tracker Initiative’s introduction to the climate debate of the concepts of ‘carbon budget’, ‘carbon bubble’, and ‘stranded assets’. These notions have shaped the financial debate around fossil fuels.

Meanwhile, the climate change think tank and advocacy organisation E3G has been popularising the concept of ‘climate diplomacy’, to explain what they do. The idea is that climate action requires more than a moral argument or a sound technical, economic evidence base. It requires political dialogue and brinkmanship.

Note that these examples all draw on metaphors – which means they can be given rich meaning with relatively little further explanation. However, the same can be achieved by coming up with a catchy phrase.

At some point, someone will have coined each of the following phrases: ‘fiscal responsibility’, ‘period poverty’, ‘revenge porn’, or even the ‘Great Gatsby curve’.

The more vivid the image, the more it will speak to politicians and the more likely it will be picked up by the media.

2. Name the policy before your opponents do it for you

We’re all familiar with examples of policies that have been undermined or even derailed by opponents through negative framing.

In the US for example, critics dubbed the estate tax the ‘Death Tax’ in the mid-1990s, in an attempt to abolish it. The tax has plummeted in the last 30 years.

In the UK, Prime Minister Theresa May’s proposed social care reform in 2017 was branded the ‘Dementia Tax’ by her critics, prompting a U-turn within 24 hours. Her Investigatory Powers Bill was nicknamed the ‘Snoopers’ Charter’, and although it was passed in 2016, it has been subject to a number of challenges in court.

In 2012, Chancellor George Osborne’s proposed simplification of VAT on hot food was derisively labelled the ‘Pasty Tax’ – culminating in a U-turn, and his entire budget being called the ‘Omnishambles Budget’.

The more vivid the image, the more it will speak to politicians and the more likely it will be picked up by the media.

These negative frames play on one of the key principles of the ‘framing effect’ – i.e. people’s aversion to loss. (This is worthy of a blog post in itself, but here are a few useful summaries by The Decision Lab, SourcesofInsight and BoyceWire.)

Meanwhile, we mentioned earlier some of the more overt examples of positive framing. These include the proposed ‘Common Sense Legal Reform Act’ (1995), or more recently Andrew Yang’s proposed ‘Freedom Dividend’ (2020). However, these examples can appear clumsy or crass outside of the US.

Successful positive framing is often altogether more subtle. This is because a sign of its success is that we’ve subconsciously adopted the frame of reference, and no longer notice it (or indeed never did).

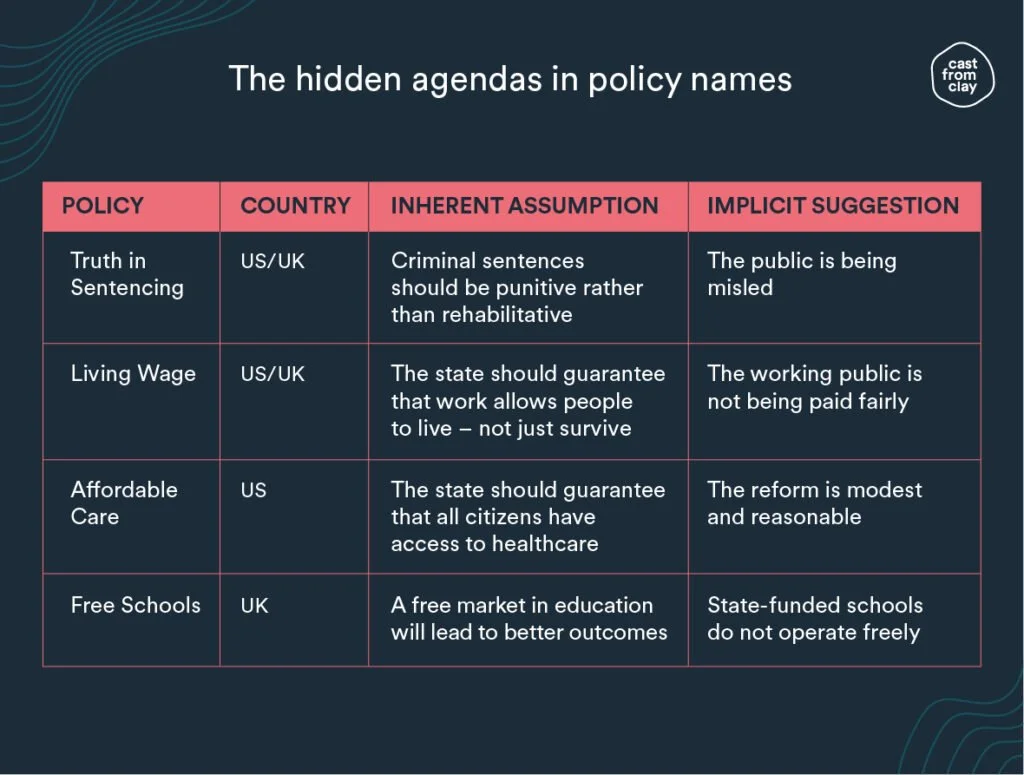

Arguably, this has been the case with policy interventions such as:

‘Truth in Sentencing’ (US & UK)

‘Living Wage’ (US & UK)

‘Affordable Care’ (US)

‘Free Schools’ (UK)

© Cast From Clay 2022

Again, someone somewhere coined each of these phrases. And whether they were consciously seeking a positive frame or instinctively happening on it, these are all instances of positive framing.

These policies’ success in terms of agenda-setting is not to say that the policies themselves were uncontroversial. Quite the opposite in fact – these examples have all been fiercely contested. But the substance of the contest was never the inherent assumption.

An interesting case study is the ‘Hostile Environment’ policy introduced by the UK Coalition government in 2012. Clearly an agenda-setting name coined to appeal to a certain section of the electorate, the inherent assumption behind the policy was that immigration needed to be curbed, and the implicit suggestion was that the UK had been too welcoming to immigrants.

Whether you see this as positive or negative framing may depend on your political views, in a way which is not true of our previous examples. The policy ultimately ended in infamy, after being denounced as a catalyst for the Windrush Scandal, which culminated in the resignation of then Home Secretary Amber Rudd.

The name served its purpose to an extent. Critics of the ‘Hostile Environment’ principle engaged with the policy on its terms. This will no doubt have entrenched the perception – at least among a section of the population – that ‘the centre’ were soft on immigration.

Ultimately, however, it did not resonate with enough of the population, prompting the incoming Home Secretary Sajid Javid to say:

“I don’t like the phrase ‘hostile’. So the terminology… is incorrect and I think it is a phrase that is unhelpful and it doesn’t represent our values as a country.”

– Sajid Javid, Senior British Politician

The name of the policy has since been changed to the ‘Compliant Environment’ policy. But its substance remains largely unchanged, according to a former Home Office official.

3. Set the frame through a metaphor

We touched on the power of metaphors earlier. We saw that choosing to liken a criminal trend to a “beast” or a “virus” can influence a policy outcome.

In fact, most of the examples we have used so far are based on metaphor. (Similes and analogies fulfil a similar purpose, they only differ in form – we use ‘metaphor’ to encompass all of these.)

In 1980, in Metaphors We Live By, George Lakoff and Mark Johnson identified how metaphors help us explain complex ideas. By associating familiar notions or experiences to abstract ideas, we are able to give them meaning.

For example, the vision of the ‘New Deal’, the ‘Great Society’, the ‘War on Drugs’ or the ‘War on Terror’ in the US; and the ‘Big Society’, the ‘Northern Powerhouse’, or the ‘Levelling Up’ agenda in the UK.

These are all useful shortcuts. By likening running a country to “running a home” and “balancing the books,” Margaret Thatcher explained the parameters for her vision of the state.

Exactly 40 years later, David Cameron’s Conservatives drew on the same metaphor to accuse the Labour Party of “not fixing the roof when the sun was shining”, following the financial crash.

The EU referendum campaign was rife with metaphor – hardly a surprise given the complexity of the issue. Leavers sought to free themselves of the “shackles” of the “EU dictatorship” and “take back control”.

Meanwhile, Remainers argued that EU membership was more like belonging to a golf club: once you leave, you can’t expect to play on the course or drink in the bar. Beware of ‘Project Fear’, answered Leavers. Brexit would deliver an ‘oven-ready deal’ as soon as the UK left.

By associating familiar notions or experiences to abstract ideas, we are able to give them meaning.

The point here is that campaigners use metaphors to explain complex ideas to a non-expert crowd. Metaphors are frames of reference – the richer the metaphor (i.e. the more ways in which it applies), the more effective it will be. If we sell our metaphor, we sell all our assumptions along with it. And we shape how people think about an issue.

The Frameworks Institute has written about metaphors extensively. Bottom line, there is no reason policy experts cannot use the same technique to explain complex ideas to non-expert politicians.

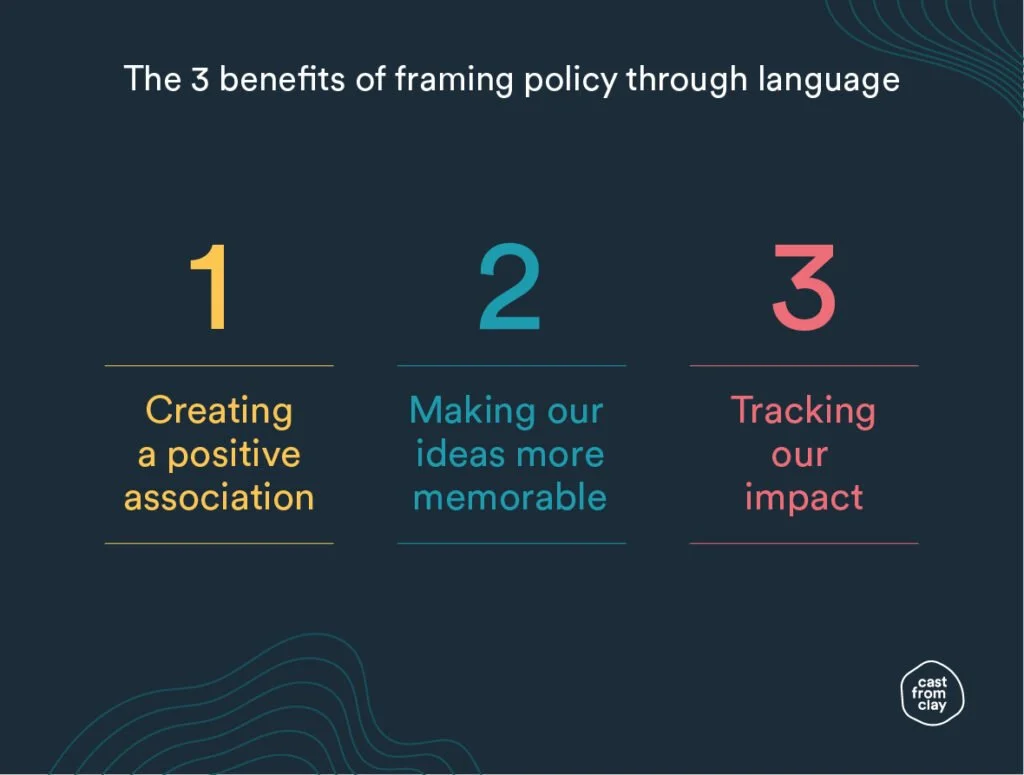

In conclusion: three benefits

Language is a key battleground for agenda-setting. She who owns the vocabulary defines the terms of the debate.

Coining key concepts, naming policies and setting the frame through metaphor(s), are all ways of seizing the initiative.

This approach has the double benefit of creating a positive association, while making our ideas more memorable – and attractive – for both politicians and media. And once traditional and social media have adopted our language, they have implicitly adopted our frame of reference.

There is a third benefit. Owning a unique phrase makes our ideas trackable. And trackable means measurable. Whether through tools like Hansard, media coverage or social media mentions, this gives us an indication of impact.

And if nothing else, surely that makes it worth it.

© Cast From Clay 2022